Law Commission report 245

Loading...

Loading...

Loading...

Loading...

Loading...

Loading...

We have been hearing that the Indian Judiciary would need decades to clear its backlog, unless the number of judges is increased multiple times and certain other reforms brought in. The judicial system has become irrelevant for the common citizens, and this is responsible for many ills plaguing our Nation, like disrespect for laws and corruption. The ease of doing business also suffers and the rule of law cannot really prevail.

Most people have started believing that this can change only if there are major judicial reforms, or judges do not give adjournments or forgo their vacations. These would require changing the attitudes of judges and lawyers and there is no sign of it happening. On the other hand a fairly popular belief is that the problem will defy any solution unless the number of judges is increased by three to four times. It appears to have been accepted that a judicial system which can deliver timebound justice is unlikely, and the fundamental right to Speedy Justice will be a mirage.

I decided to look at the data and analyse it to arrive at the number of judges required. The 20th Law Commission in its report no. 245 submitted in July 2014, after examining the issue from different perspectives has come to the conclusion that the Rate of Disposal per judge per year is the right method for evaluating this. In simple terms it assumes that if ten judges dispose 1000 cases, 12 judges will dispose 1200 cases. I took the data reported by the Law Commission in its report no. 245, and did that a proper analysis of its data for 2002 to 2012 of fourteen states for the subordinate courts it had taken. It shows that if it had been ensured that all sanctioned positions of judges were filled there would have been no backlog by 2007[1]. This would mean the queue would disappear and it would be possible to devote adequate time to all cases without having to wait. In most cases it may be possible to dispose cases in less than 3 months.

I decided to also take a look at this issue by analyzing the data given on the Supreme Court’s website at http://www.supremecourt.gov.in/publication for a ten year period from 2006 to 2015 which has a quarterly report for all the courts.[2] The summary of this analysis is tabulated below[3]. This shows that the number of sanctioned judges is adequate and if all the sanctioned judges were appointed mounting pendency would be history.

The number of judges sanctioned in the three levels on 31 December 2015 was 31, 1018 and 20620, whereas the actual number of judges was 26, 598 and 16119. Thus the total number of sanctioned posts were 21669 whereas the working judges were only 16743! Filling about 5000 vacant positions can make the judicial system deliver efficiently.

Another way of looking at this data is, for the ten year period from 2009 to 2013:

| Supreme Court | High Courts | Subordinate

Courts |

Total | ||

| 2006 | 34481 | 3521283 | 25654251 | 29212021 | Pending cases |

| 2015 | 59272 | 4225640 | 27652918 | 31939845 | Pending cases |

| During the ten year | Period 2006 | To 2015 | Total | ||

| Cases Instituted | 755082

|

18021327

|

175649101

|

194425510

|

|

| Cases Disposed | 730420

|

16539732

|

173362326

|

190632478

|

|

| Pendency

Increase |

24662

|

1481595

|

2286775

|

3793032

|

|

| Missed disposal

Due to Vacancy |

73042

|

5127317

|

34672465

|

39872824

|

The increase in pendency in ten years was about 38 lac cases whereas the disposal missed due to not filling all sanctioned posts was nearly 400 lacs!

There can be no excuse for keeping judicial positions vacant while the nation suffers because of this neglect. The retirement date of judges is well known. The process of selecting new judges can start six months ahead for those retiring. We need just about 22000 judges. Even if infrastructure is inadequate it would need to be augmented by only about 20%. This is a simple solution and can be implemented very easily. This does not assume any change in the way judges and lawyers function. It only assumes that the extra judges who fill the vacancies will also dispose matters at the same rate as those who are already in the system. The average rate of disposal for the lower court judges taking the data of the Law Commission for eleven years from 2002 to 2012 gives an average rate of 1380 cases per year. On the other hand rate of disposal for all the subordinate courts for the ten year period 2006 to 2015 gives a rate of 1232. This is a variance of just about 12%. This shows that over a reasonably long period all the variability of cases would even out.

For the sake of the nation all those responsible must ensure that all judicial appointments are made in a timely manner. An easy solution is available. This analysis suggests that if a simple discipline of ensuring zero vacancy is followed, the sanctioned strength is adequate to dispose the inflow of cases and some backlog. Even if we assume that there would be upto 5% vacancies, the backlogs would go down. If this simple solution is implemented the problem will move towards a resolution.

Shailesh Gandhi; former Central Information Commissioner, shaileshgan@gmail.com

8976240798

[1] 2 Delivery of Justice Law Comm. Sheet 1

[2] 3 Pendency SC website Sheet 1Supreme Court; 2 High Courts; 3 Subordinate Courts

[3] 3 Pendency of SC website sheet 4

BY INVITATION – Don’t need 70,000 judges. Just fill vacancies to cut backlog

SHAILESH GANDHI

Everyone agrees that judicial pendency is a serious problem in India.Most of the suggested big-ticket reforms call for major changes in the way the judiciary and bar function, way the judiciary and bar function, and a threeto four-fold increase in the sanctioned strength of judges. On the ground, though, nothing has changed. It is almost as if we have come to accept that the problem cannot be solved.

To understand why the right to speedy justice -recognized as a fundamental right by our courts -is violated in India, I analysed data from January 2009 to September 2015. The information was taken from the Supreme Court’s website (http:supremecourtofindia.nic.incourtnews.htm) and the idea was to deter mine how many judges would be required to dispose of incoming cases as well as reduce the backlog -assuming there is no change in functioning, adjournments and judges’ vacations. The analysis exposes several myths about the justice system:

MYTH 1:

India needs more prisons as the ones we have are overcrowded with criminals -4.2 lakh in 2014, against a capacity of 3.6 lakh.

FACT:

Only 1.3 lakh prisoners were convicts. The rest were undertrials, most of them poor. And in many cases, their only `crime’ perhaps was poverty .

Many of them were like Tukaram, whose story was recounted to me by a prison volunteer. Tukaram, 27, came to Mumbai from a village in Vidarbha. He dreamt of earning enough so his wife and one-year-old daughter wouldn’t have to go hungry . While sleeping on the footpath one night, he was picked up by the police and put in jail. Tukaram had no idea what crime he had been arrested for. He managed to send a postcard to his wife, who sent back a reply saying she could not come as she had no money . Sometimes Tukaram was taken to the court, but he did not understand what was happening. After six years, a sympathetic lawyer heard his story and got him released. Tukaram went back to his village and found his daughter had died and his wife had married a 60-year-old widower. A broken man, he committed suicide.

MYTH 2:

Backlog in courts is increasing at a galloping pace. “There are over three crore cases pending and it might take 320 years to clear these.“ This statement by Justice V V Rao of Andhra Pradesh has been quoted extensively .

FACT:

Every year about two crore cases are instituted and a similar number decided by the courts. Between January 2009 and September 2015, the backlog increased from 303 lakh to only 312 lakh. While talking of a backlog of three crore cases we do not realize that each year our courts dispose around two crore.

MYTH 3:

We need 70,000 judges instead of the sanctioned 21,542 to clear the backlog.

FACT:

That’s complete fiction. The average vacancies in sanctioned positions of judges in this period were about 21%, whereas backlog increase was less than 1.5% per year. If the judicial positions had been filled, the backlog would have gone down to less than one crore cases.

MYTH 4:

The government is solely at fault for not appointing enough judges.

FACT:

Though there are 462 vacancies in high courts currently, the judges’ collegium has only recommended 170 names. Neither the government nor the judiciary has paid attention to the simple fact that merely ensuring zero vacancy in judicial positions would lead to reduction in backlog.

Some argue that it is difficult to find good people to fill vacancies of judges. If India cannot find 21,542 judges, what purpose will be served by sanctioning 70,000 judges? Large companies in India sometimes hire more than 10,000 persons in a single year, for jobs requiring both logical thinking and ethical standards.

MYTH 5:

Unless major judicial reforms take place, the backlog will remain.

FACT:

Judicial reforms will help, but a simple, doable solution exists already . All it takes is will.

MYTH 6:

The judiciary cannot force the government to fill vacancies.

FACT:

As far as the Supreme Court and high courts are concerned, selection is only done by the collegium. So this is clearly the responsibility of the judiciary . In the case of lower courts, it is a joint exercise. The judiciary had recently ordered the government to fill up vacancies in the Central Information Commission and the order was complied with. The apex court can certainly do the same for judicial vacancies.

These myths need to be dumped and the judiciary must accept its primary responsibility of ensuring fewer delays by appointing judges as sanctioned.

The writer is a former central information commissioner

Presently there is considerable focus being paid to the Judicial accountability and Judicial appointments bills. These are necessary but do they address the biggest problem of the judicial system? The biggest problem of our judicial system is that it does not deliver in any reasonable time. Consequently over 80% of Indians will not approach the courts, unless they are trapped by the system. If a poor man is implicated in a civil or criminal case he is unwillingly trapped, since there is no time limit for the judicial system. The respect for rule of law has almost disappeared since the powerful can ensure that they will never have to pay for their crimes, even if they are caught.

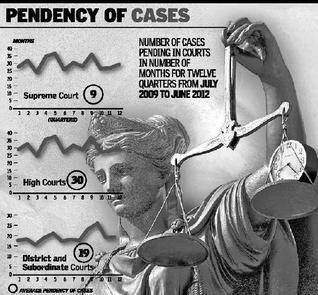

The Chief Justice has rightly refused to fast track only cases against MPs, since it effectively means pushing the others back in the queue. The Supreme Court needs to make a commitment on how it would deliver timebound justice and what would be required for this. I decided to take a look at the issue by doing some number crunching with the objective of trying to estimate the number of judges required. Data has been taken from the Supreme Court website for twelve quarters from July 2009 to June 2012.

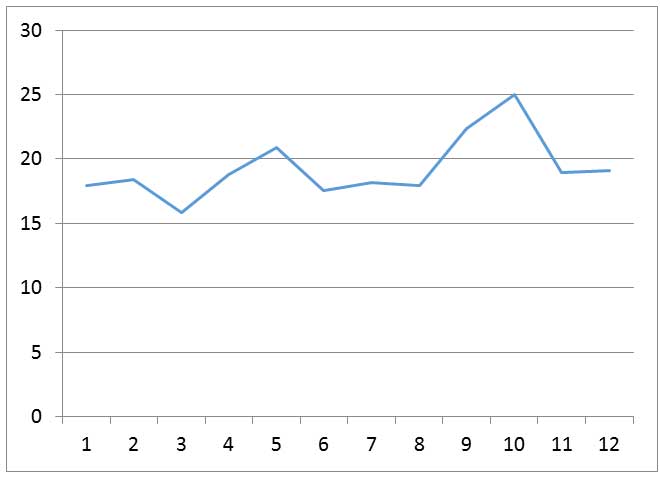

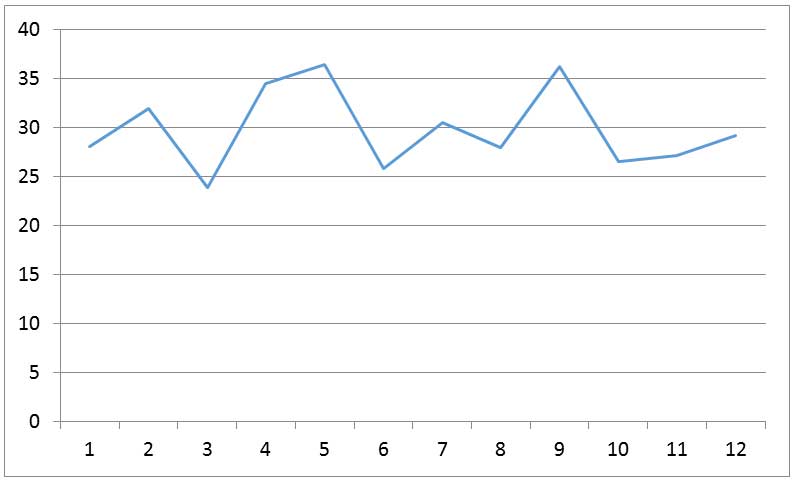

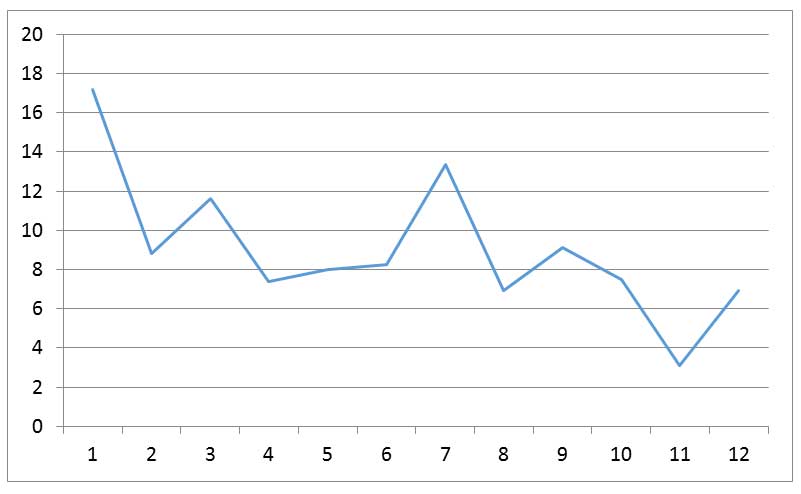

I noted the new cases Instituted in each quarter, disposal and the pending cases in the Supreme Court, High Court and the District & Subordinate Courts. Using simple arithmetic it is possible to get the number of months’ pendency. I have calculated for each quarter, and in no case did the backlog appear to be over 36 months. The average pendency for the Supreme Court, High Court and the District & Subordinate Courts for the period July 2009 to June 2012 comes to 9 months 30 months and 19 months respectively. The legal profession is aghast when one talks about measuring such numbers, on the ground that the differences in cases is vast. However, over a large number of courts and cases, the large variations due to different cases would even out and can be used to compare or find possible solutions. Besides the evaluation is based on 12 quarters over three years, and appears to show some consistency as revealed in the graphs.

This appears to indicate that if the principle of ‘First In First Out’ (FIFO) could be strictly followed, this may be the time for a case to go through the Courts. This would not be feasible completely, but there can be no justification for many cases taking more than double the average time in the Courts. The Courts should lay down a discipline that almost no case could be allowed to languish for more than double the average time taken for disposals. Presently the listing of cases is being done by the judges, and no humanbeing can really do this exercise rationally, given the mass of data. It would be sensible to devise a fair criterion and incorporate this in computer software, which would list the cases and also give the dates for adjournments based on a predetermined rational basis. This would result in removing much of the arbitrariness, and also reduce the power of some lawyers to hasten or delay cases as per their will. If this was done, the maximum time at the three Courts would be 18 months, 60 months and 38 months.

The average vacancies in the three levels are 15% for the Supreme Court, 30% for the High Courts and over 20% for the lower courts. When citizens are suffering acutely because of the huge delays in the judicial system, there can be no justification for such high levels of sanctioned positions being vacant. The dates of retirement of judges are known in advance and hence the vacancies are largely because of neglect. After filling the vacancies, if the Courts stick to their avowed judgements to allow adjournments rarely, it should certainly be possible to increase the disposals by atleast 20%. If Courts basically follow the principle of dealing with cases primarily on a FIFO basis, the judiciary could deliver in a reasonable time.

My suggestions based on the above are given below.

Main suggestions:

Secondary suggestions:

This would be meaningful judicial accountability.

Shailesh Gandhi

Former Central Information Commissioner.

Revving up the judicial juggernaut 19 August 2014 Oped

हिन्दी समाचार – समाचार लेख Google हिंदी वेब अभी hindiweb.com

SHAILESH GANDHI

With citizens suffering acutely because of delays in court trials, it is time to fix accountability of the judges

Recently, the Supreme Court refused to fast-track criminal cases against Members of Parliament, saying the manpower in trial courts and infrastructure was inadequate. Prime Minister Narendra Modi had, on June 11, sought to expedite trials of pending cases against MPs within a year. But that could have meant pushing other cases back in the queue. As the apex court rightly observed, there are other categories where criminal trials need to be expedited, such as women and senior citizens.

The Supreme Court needs to make a commitment on the need to deliver time-bound justice. But is that possible?

Analysis of data

To understand this, I did some number crunching, with the objective of trying to estimate the number of judges required for deliverance of justice on time. I used the Supreme Court data for 12 quarters, from July 2009 to June 2012.

I made note of new cases instituted in each quarter and disposed and pending cases in the Supreme Court, High Courts and district and subordinate courts. I divided the number of cases disposed per quarter to arrive at the figure of average monthly disposal of cases. Then I divided the number of pending cases with this figure to estimate monthly pendency.

For each quarter, I realised, no case appeared in backlog for more than 36 months. And yet, many people have had cases continuing for over 10 years because of no adherence to chronologically clear cases.

The average pendency for the Supreme Court, High Courts and district and subordinate courts for the period July 2009 to June 2012 comes to 9 months, 30 months, and 19 months respectively.

The legal profession is aghast when one talks about measuring such numbers, on the ground that the differences in cases is vast. Many in the legal fraternity say one cannot apply mathematical analysis to understand this. However, over a large number of courts and cases, the large variations due to different cases would even out and can be used to compare or find possible solutions.

Besides, the evaluation is based on 12 quarters over three years, and appears to show some consistency. This data appears to show some consistency as the graphs show.

This appears to indicate that if the principle of ‘first in, first out’ (FIFO) could be strictly followed, this may be the time required to decide a case in a court.

This would not be feasible completely, but there can be no justification for many cases taking more than double the average time in the courts. Courts should lay down a discipline that almost no case should be allowed to languish for more than double the average time taken for disposals. At present, the listing of cases is being done by the judges, and no human being can really do this exercise rationally, given the mass of data. It would be sensible to devise a fair criterion and incorporate this in computer software, which would list the cases and also give the dates for adjournments based on a rational basis. This would result in removing much of the arbitrariness and also reduce the power of some lawyers to hasten or delay cases as per their will. If done, the maximum time the three courts would take to decide on a case would be 18 months, 60 months, and 38 months. The average vacancies in the three levels are 15 per cent for the Supreme Court, 30 per cent for the High Courts and over 20 per cent for the district and subordinate courts.

Filling in vacancies

When citizens are suffering acutely because of the huge delays in the judicial system, there can be no justification for such high levels of sanctioned positions being vacant. The dates of retirement of judges are known in advance and hence the vacancies are largely because of neglect. After filling the vacancies, if courts stick to their avowed judgments to allow adjournments rarely, it should certainly be possible to increase the disposals by at least 20 per cent. Basically, if courts follow the principle of FIFO, the judiciary could deliver in a reasonable time.

That is why courts must accept the discipline that over 95 per cent of the cases will be settled in less than double the average pendency. Then, reasonable equity could be provided to citizens and Article 14 actualised in courts. The listing of cases should be done by a computer programme, with judges having the discretion to override it in only 5 per cent of cases.

Also, vacancies in the sanctioned strength of judges should be less than 5 per cent. Adjournments should be rare, and the maximum number ought to be fixed by a computer. A calculation can be done to see the number of judges required to bring the average pendency in all courts to less than one year. Most probably, an increase of about 20 per cent judges in High Courts and lower judiciary could bring down the average pendency to less than a year. The number of disposals per judge and per court along with data of pending cases, giving details of the periods since institution, should be displayed by the courts on their websites.

That would be meaningful judicial accountability.

(Shailesh Gandhi is former Central Information Commissioner.)

Courts should lay down a discipline that almost no case should be allowed to languish for more than double the average time taken for disposals