Delivery Of Justice

Justice can be delivered in reasonable time without undertaking Major Reforms

We have been hearing that the Indian Judiciary would need decades to clear its backlog, unless the number of judges is increased multiple times and certain other reforms brought in. The judicial system has become irrelevant for the common citizens, and this is responsible for many ills plaguing our Nation, like disrespect for laws and corruption. The ease of doing business also suffers and the rule of law cannot really prevail.

Most people have started believing that this can change only if there are major judicial reforms, or judges do not give adjournments or forgo their vacations. These would require changing the attitudes of judges and lawyers and there is no sign of it happening. On the other hand a fairly popular belief is that the problem will defy any solution unless the number of judges is increased by three to four times. It appears to have been accepted that a judicial system which can deliver timebound justice is unlikely, and the fundamental right to Speedy Justice will be a mirage.

I decided to look at the data and analyse it to arrive at the number of judges required. The 20th Law Commission in its report no. 245 submitted in July 2014, after examining the issue from different perspectives has come to the conclusion that the Rate of Disposal per judge per year is the right method for evaluating this. In simple terms it assumes that if ten judges dispose 1000 cases, 12 judges will dispose 1200 cases. I took the data reported by the Law Commission in its report no. 245, and did that a proper analysis of its data for 2002 to 2012 of fourteen states for the subordinate courts it had taken. It shows that if it had been ensured that all sanctioned positions of judges were filled there would have been no backlog by 2007[1]. This would mean the queue would disappear and it would be possible to devote adequate time to all cases without having to wait. In most cases it may be possible to dispose cases in less than 3 months.

I decided to also take a look at this issue by analyzing the data given on the Supreme Court’s website at http://www.supremecourt.gov.in/publication for a ten year period from 2006 to 2015 which has a quarterly report for all the courts.[2] The summary of this analysis is tabulated below[3]. This shows that the number of sanctioned judges is adequate and if all the sanctioned judges were appointed mounting pendency would be history.

The number of judges sanctioned in the three levels on 31 December 2015 was 31, 1018 and 20620, whereas the actual number of judges was 26, 598 and 16119. Thus the total number of sanctioned posts were 21669 whereas the working judges were only 16743! Filling about 5000 vacant positions can make the judicial system deliver efficiently.

Another way of looking at this data is, for the ten year period from 2009 to 2013:

| Supreme Court | High Courts | Subordinate

Courts |

Total | ||

| 2006 | 34481 | 3521283 | 25654251 | 29212021 | Pending cases |

| 2015 | 59272 | 4225640 | 27652918 | 31939845 | Pending cases |

| During the ten year | Period 2006 | To 2015 | Total | ||

| Cases Instituted | 755082

|

18021327

|

175649101

|

194425510

|

|

| Cases Disposed | 730420

|

16539732

|

173362326

|

190632478

|

|

| Pendency

Increase |

24662

|

1481595

|

2286775

|

3793032

|

|

| Missed disposal

Due to Vacancy |

73042

|

5127317

|

34672465

|

39872824

|

The increase in pendency in ten years was about 38 lac cases whereas the disposal missed due to not filling all sanctioned posts was nearly 400 lacs!

There can be no excuse for keeping judicial positions vacant while the nation suffers because of this neglect. The retirement date of judges is well known. The process of selecting new judges can start six months ahead for those retiring. We need just about 22000 judges. Even if infrastructure is inadequate it would need to be augmented by only about 20%. This is a simple solution and can be implemented very easily. This does not assume any change in the way judges and lawyers function. It only assumes that the extra judges who fill the vacancies will also dispose matters at the same rate as those who are already in the system. The average rate of disposal for the lower court judges taking the data of the Law Commission for eleven years from 2002 to 2012 gives an average rate of 1380 cases per year. On the other hand rate of disposal for all the subordinate courts for the ten year period 2006 to 2015 gives a rate of 1232. This is a variance of just about 12%. This shows that over a reasonably long period all the variability of cases would even out.

For the sake of the nation all those responsible must ensure that all judicial appointments are made in a timely manner. An easy solution is available. This analysis suggests that if a simple discipline of ensuring zero vacancy is followed, the sanctioned strength is adequate to dispose the inflow of cases and some backlog. Even if we assume that there would be upto 5% vacancies, the backlogs would go down. If this simple solution is implemented the problem will move towards a resolution.

Shailesh Gandhi; former Central Information Commissioner, shaileshgan@gmail.com

8976240798

[1] 2 Delivery of Justice Law Comm. Sheet 1

[2] 3 Pendency SC website Sheet 1Supreme Court; 2 High Courts; 3 Subordinate Courts

[3] 3 Pendency of SC website sheet 4

TOI 70K judges

May 29 2016 : The Times of India (Delhi)

BY INVITATION – Don’t need 70,000 judges. Just fill vacancies to cut backlog

SHAILESH GANDHI

Everyone agrees that judicial pendency is a serious problem in India.Most of the suggested big-ticket reforms call for major changes in the way the judiciary and bar function, way the judiciary and bar function, and a threeto four-fold increase in the sanctioned strength of judges. On the ground, though, nothing has changed. It is almost as if we have come to accept that the problem cannot be solved.

To understand why the right to speedy justice -recognized as a fundamental right by our courts -is violated in India, I analysed data from January 2009 to September 2015. The information was taken from the Supreme Court’s website (http:supremecourtofindia.nic.incourtnews.htm) and the idea was to deter mine how many judges would be required to dispose of incoming cases as well as reduce the backlog -assuming there is no change in functioning, adjournments and judges’ vacations. The analysis exposes several myths about the justice system:

MYTH 1:

India needs more prisons as the ones we have are overcrowded with criminals -4.2 lakh in 2014, against a capacity of 3.6 lakh.

FACT:

Only 1.3 lakh prisoners were convicts. The rest were undertrials, most of them poor. And in many cases, their only `crime’ perhaps was poverty .

Many of them were like Tukaram, whose story was recounted to me by a prison volunteer. Tukaram, 27, came to Mumbai from a village in Vidarbha. He dreamt of earning enough so his wife and one-year-old daughter wouldn’t have to go hungry . While sleeping on the footpath one night, he was picked up by the police and put in jail. Tukaram had no idea what crime he had been arrested for. He managed to send a postcard to his wife, who sent back a reply saying she could not come as she had no money . Sometimes Tukaram was taken to the court, but he did not understand what was happening. After six years, a sympathetic lawyer heard his story and got him released. Tukaram went back to his village and found his daughter had died and his wife had married a 60-year-old widower. A broken man, he committed suicide.

MYTH 2:

Backlog in courts is increasing at a galloping pace. “There are over three crore cases pending and it might take 320 years to clear these.“ This statement by Justice V V Rao of Andhra Pradesh has been quoted extensively .

FACT:

Every year about two crore cases are instituted and a similar number decided by the courts. Between January 2009 and September 2015, the backlog increased from 303 lakh to only 312 lakh. While talking of a backlog of three crore cases we do not realize that each year our courts dispose around two crore.

MYTH 3:

We need 70,000 judges instead of the sanctioned 21,542 to clear the backlog.

FACT:

That’s complete fiction. The average vacancies in sanctioned positions of judges in this period were about 21%, whereas backlog increase was less than 1.5% per year. If the judicial positions had been filled, the backlog would have gone down to less than one crore cases.

MYTH 4:

The government is solely at fault for not appointing enough judges.

FACT:

Though there are 462 vacancies in high courts currently, the judges’ collegium has only recommended 170 names. Neither the government nor the judiciary has paid attention to the simple fact that merely ensuring zero vacancy in judicial positions would lead to reduction in backlog.

Some argue that it is difficult to find good people to fill vacancies of judges. If India cannot find 21,542 judges, what purpose will be served by sanctioning 70,000 judges? Large companies in India sometimes hire more than 10,000 persons in a single year, for jobs requiring both logical thinking and ethical standards.

MYTH 5:

Unless major judicial reforms take place, the backlog will remain.

FACT:

Judicial reforms will help, but a simple, doable solution exists already . All it takes is will.

MYTH 6:

The judiciary cannot force the government to fill vacancies.

FACT:

As far as the Supreme Court and high courts are concerned, selection is only done by the collegium. So this is clearly the responsibility of the judiciary . In the case of lower courts, it is a joint exercise. The judiciary had recently ordered the government to fill up vacancies in the Central Information Commission and the order was complied with. The apex court can certainly do the same for judicial vacancies.

These myths need to be dumped and the judiciary must accept its primary responsibility of ensuring fewer delays by appointing judges as sanctioned.

The writer is a former central information commissioner

Like the article: SMS MTMVCOL Yes or No to 58888@ 3sms

Timebound Justice

Presently there is considerable focus being paid to the Judicial accountability and Judicial appointments bills. These are necessary but do they address the biggest problem of the judicial system? The biggest problem of our judicial system is that it does not deliver in any reasonable time. Consequently over 80% of Indians will not approach the courts, unless they are trapped by the system. If a poor man is implicated in a civil or criminal case he is unwillingly trapped, since there is no time limit for the judicial system. The respect for rule of law has almost disappeared since the powerful can ensure that they will never have to pay for their crimes, even if they are caught.

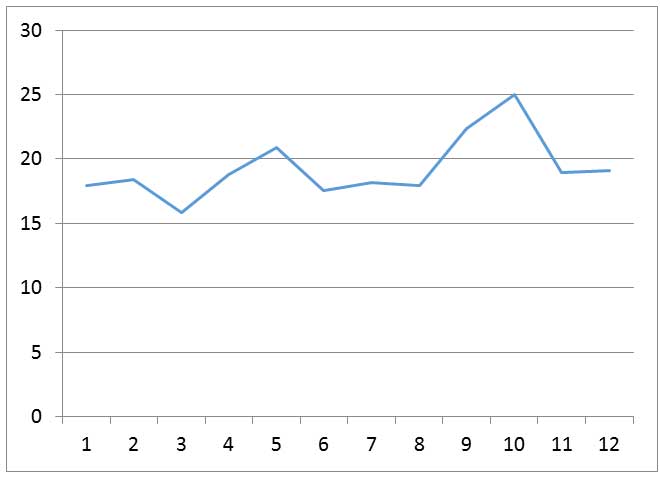

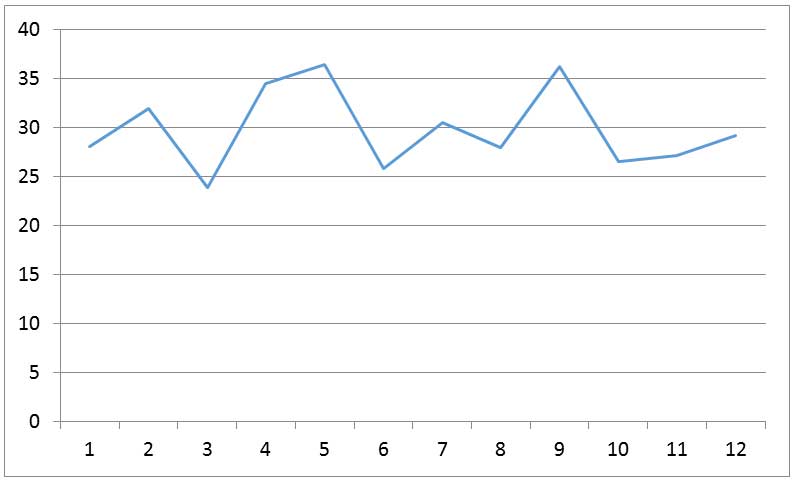

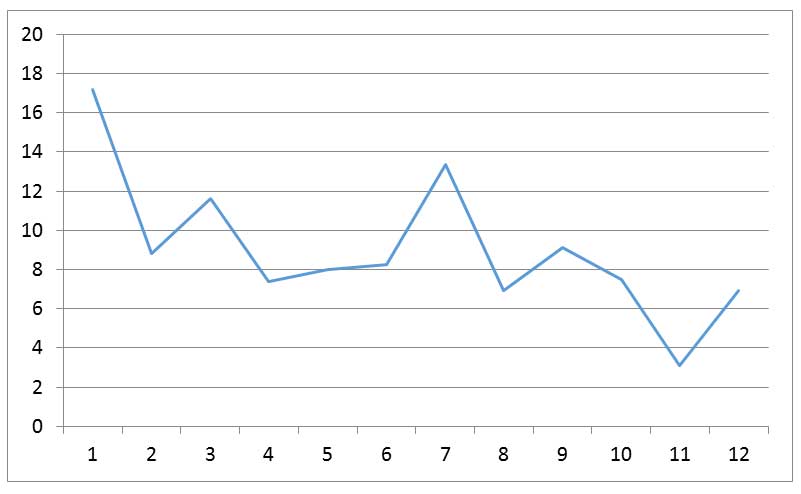

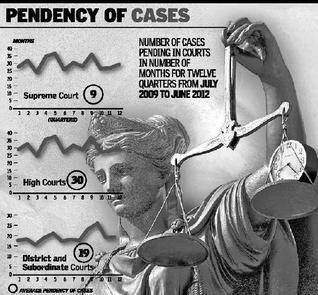

The Chief Justice has rightly refused to fast track only cases against MPs, since it effectively means pushing the others back in the queue. The Supreme Court needs to make a commitment on how it would deliver timebound justice and what would be required for this. I decided to take a look at the issue by doing some number crunching with the objective of trying to estimate the number of judges required. Data has been taken from the Supreme Court website for twelve quarters from July 2009 to June 2012.

I noted the new cases Instituted in each quarter, disposal and the pending cases in the Supreme Court, High Court and the District & Subordinate Courts. Using simple arithmetic it is possible to get the number of months’ pendency. I have calculated for each quarter, and in no case did the backlog appear to be over 36 months. The average pendency for the Supreme Court, High Court and the District & Subordinate Courts for the period July 2009 to June 2012 comes to 9 months 30 months and 19 months respectively. The legal profession is aghast when one talks about measuring such numbers, on the ground that the differences in cases is vast. However, over a large number of courts and cases, the large variations due to different cases would even out and can be used to compare or find possible solutions. Besides the evaluation is based on 12 quarters over three years, and appears to show some consistency as revealed in the graphs.

This appears to indicate that if the principle of ‘First In First Out’ (FIFO) could be strictly followed, this may be the time for a case to go through the Courts. This would not be feasible completely, but there can be no justification for many cases taking more than double the average time in the Courts. The Courts should lay down a discipline that almost no case could be allowed to languish for more than double the average time taken for disposals. Presently the listing of cases is being done by the judges, and no humanbeing can really do this exercise rationally, given the mass of data. It would be sensible to devise a fair criterion and incorporate this in computer software, which would list the cases and also give the dates for adjournments based on a predetermined rational basis. This would result in removing much of the arbitrariness, and also reduce the power of some lawyers to hasten or delay cases as per their will. If this was done, the maximum time at the three Courts would be 18 months, 60 months and 38 months.

The average vacancies in the three levels are 15% for the Supreme Court, 30% for the High Courts and over 20% for the lower courts. When citizens are suffering acutely because of the huge delays in the judicial system, there can be no justification for such high levels of sanctioned positions being vacant. The dates of retirement of judges are known in advance and hence the vacancies are largely because of neglect. After filling the vacancies, if the Courts stick to their avowed judgements to allow adjournments rarely, it should certainly be possible to increase the disposals by atleast 20%. If Courts basically follow the principle of dealing with cases primarily on a FIFO basis, the judiciary could deliver in a reasonable time.

My suggestions based on the above are given below.

Main suggestions:

- Courts must accept the discipline that over 95% of the cases will be settled in less than double the average pendency. Then, reasonable equity could be provided to citizens, and Article 14 actualized in the Courts.

- The listing of cases should be done by a computer program, with judges having the discretion to override it in only 5% cases.

Secondary suggestions:

- Vacancies in the sanctioned strength of judges should be less than 5%.

- Adjournments should be rare and maximum number fixed by a computer. Even when an adjournment is given the next date should be given by the computer program.

- A calculation could be done to see the number of judges required to bring the average pendency in all Courts to less than one year. Most probably an increase of about 20% judges in the High Courts and lower judiciary could bring down the average pendency to less than a year.

- Disposal per judge and Court alongwith data of pending cases giving details of the periods since Institution should be displayed by the Courts on their websites.

This would be meaningful judicial accountability.

Shailesh Gandhi

Former Central Information Commissioner.

Pendency of Cases in Courts in number of months for twelve quarters

From July 2009 to June 2012

Note: Horizontal axis shows quarters whereas the vertical axis represents number of months pendency.

-

-

District and Subordinate Courts

-

High Courts

-

Supreme Courts

-

Timebound Hindu Article

Revving up the judicial juggernaut 19 August 2014 Oped

हिन्दी समाचार – समाचार लेख Google हिंदी वेब अभी hindiweb.com

SHAILESH GANDHI

With citizens suffering acutely because of delays in court trials, it is time to fix accountability of the judges

Recently, the Supreme Court refused to fast-track criminal cases against Members of Parliament, saying the manpower in trial courts and infrastructure was inadequate. Prime Minister Narendra Modi had, on June 11, sought to expedite trials of pending cases against MPs within a year. But that could have meant pushing other cases back in the queue. As the apex court rightly observed, there are other categories where criminal trials need to be expedited, such as women and senior citizens.

The Supreme Court needs to make a commitment on the need to deliver time-bound justice. But is that possible?

Analysis of data

To understand this, I did some number crunching, with the objective of trying to estimate the number of judges required for deliverance of justice on time. I used the Supreme Court data for 12 quarters, from July 2009 to June 2012.

I made note of new cases instituted in each quarter and disposed and pending cases in the Supreme Court, High Courts and district and subordinate courts. I divided the number of cases disposed per quarter to arrive at the figure of average monthly disposal of cases. Then I divided the number of pending cases with this figure to estimate monthly pendency.

For each quarter, I realised, no case appeared in backlog for more than 36 months. And yet, many people have had cases continuing for over 10 years because of no adherence to chronologically clear cases.

The average pendency for the Supreme Court, High Courts and district and subordinate courts for the period July 2009 to June 2012 comes to 9 months, 30 months, and 19 months respectively.

The legal profession is aghast when one talks about measuring such numbers, on the ground that the differences in cases is vast. Many in the legal fraternity say one cannot apply mathematical analysis to understand this. However, over a large number of courts and cases, the large variations due to different cases would even out and can be used to compare or find possible solutions.

Besides, the evaluation is based on 12 quarters over three years, and appears to show some consistency. This data appears to show some consistency as the graphs show.

This appears to indicate that if the principle of ‘first in, first out’ (FIFO) could be strictly followed, this may be the time required to decide a case in a court.

This would not be feasible completely, but there can be no justification for many cases taking more than double the average time in the courts. Courts should lay down a discipline that almost no case should be allowed to languish for more than double the average time taken for disposals. At present, the listing of cases is being done by the judges, and no human being can really do this exercise rationally, given the mass of data. It would be sensible to devise a fair criterion and incorporate this in computer software, which would list the cases and also give the dates for adjournments based on a rational basis. This would result in removing much of the arbitrariness and also reduce the power of some lawyers to hasten or delay cases as per their will. If done, the maximum time the three courts would take to decide on a case would be 18 months, 60 months, and 38 months. The average vacancies in the three levels are 15 per cent for the Supreme Court, 30 per cent for the High Courts and over 20 per cent for the district and subordinate courts.

Filling in vacancies

When citizens are suffering acutely because of the huge delays in the judicial system, there can be no justification for such high levels of sanctioned positions being vacant. The dates of retirement of judges are known in advance and hence the vacancies are largely because of neglect. After filling the vacancies, if courts stick to their avowed judgments to allow adjournments rarely, it should certainly be possible to increase the disposals by at least 20 per cent. Basically, if courts follow the principle of FIFO, the judiciary could deliver in a reasonable time.

That is why courts must accept the discipline that over 95 per cent of the cases will be settled in less than double the average pendency. Then, reasonable equity could be provided to citizens and Article 14 actualised in courts. The listing of cases should be done by a computer programme, with judges having the discretion to override it in only 5 per cent of cases.

Also, vacancies in the sanctioned strength of judges should be less than 5 per cent. Adjournments should be rare, and the maximum number ought to be fixed by a computer. A calculation can be done to see the number of judges required to bring the average pendency in all courts to less than one year. Most probably, an increase of about 20 per cent judges in High Courts and lower judiciary could bring down the average pendency to less than a year. The number of disposals per judge and per court along with data of pending cases, giving details of the periods since institution, should be displayed by the courts on their websites.

That would be meaningful judicial accountability.

(Shailesh Gandhi is former Central Information Commissioner.)

Courts should lay down a discipline that almost no case should be allowed to languish for more than double the average time taken for disposals

RTI constricted

Right To Information constricted

RTI usage and propagation is moving at a fast pace because of citizen enthusiasm and desire for accountable governance. The biggest gain has been in empowering individual citizens to translate the promise of ‘democracy of the people, by the people, for the people’ into a living reality. The law as framed by Parliament has outstandingly codified this fundamental right of citizens. When framing the law cognizance had been taken of various landmark decisions of the Supreme Court on this subject. One of the objectives of this law mentioned in its preamble is to contain corruption. It is a simple, easy to understand statute, which common people can understand. However, there are some decisions of information commissions and courts which are constricting this fundamental right of citizens which is neither sanctioned by the constitution or the law. This paper is an effort to highlight one such instance,- the Girish Ramchandra Deshpande judgment,- which is resulting in an effective amendment of the law without Parliamentary sanction. The denial of information has been justified on the basis of Section 8 (1) (j) which allows denial of information, when:

- information which relates to personal information the disclosure of which has no relationship to any public activity or interest, or which would cause unwarranted invasion of the privacy of the individual unless the Central Public Information Officer or the State Public Information Officer or the appellate authority, as the case may be, is satisfied that the larger public interest justifies the disclosure of such information:

Provided that the information, which cannot be denied to the Parliament or a State Legislature shall not be denied to any person.

The RTI Act mandates that all citizens have the right to information subject to the provisions of the Act. Section 7 (1) clearly states that information can only be refused for the reasons specified in Section 8 and 9. Section 22 of the Act ensures that no prior laws or rules can be used to deny information. I would also draw attention to the fact that the reasonable restrictions which may be placed on the freedom of expression under Article 19 (1) (a) have been mentioned in Article 19 (2) in the constitution as affecting “the interests of the sovereignty and integrity of India, the security of the State, friendly relations with foreign States, public order, decency or morality or in relation to contempt of court, defamation or incitement to an offence.”

It is worth remembering two judgments of the Supreme Court. A five judge bench has ruled in P. Ramachandra Rao v. State of Karnataka case no. appeal (crl.) 535.: “Courts can declare the law, they can interpret the law, they can remove obvious lacunae and fill the gaps but they cannot entrench upon in the field of legislation properly meant for the legislature”. In Rajiv Singh Dalal (Dr.) Vs. Chaudhari Devilal University, Sirsa and another (2008), the Supreme Court, after referring to its earlier decisions, has observed as follows. “The decision of a Court is a precedent, if it lays down some principle of law supported by reasons. Mere casual observations or directions without laying down any principle of law and without giving reasons does not amount to a precedent.”

The Supreme Court’s judgment in the Girish Ramchandra Deshpande[1] judgment is being treated as the law throughout the country and I will argue that this has the effect of amending Section 8 (1) (j) without legitimacy. This paper will seek to show that the impugned judgment does not lay down the law and is being wrongly used to constrict the citizen’s fundamental right to information.

Girish Ramchandra Deshpande had sought copies of memos, show cause notices and censure/punishment awarded to a public servant. He had also demanded details of assets and gifts received by him. Since the Central Information Commission gave an adverse ruling he finally went to the Supreme Court. The main part of the judgment states:

“12. The petitioner herein sought for copies of all memos, show cause notices and censure/punishment awarded to the third respondent from his employer and also details viz. movable and immovable properties and also the details of his investments, lending and borrowing from Banks and other financial institutions. Further, he has also sought for the details of gifts stated to have accepted by the third respondent, his family members and friends and relatives at the marriage of his son. The information mostly sought for finds a place in the income tax returns of the third respondent. The question that has come up for consideration is whether the above-mentioned information sought for qualifies to be “personal information” as defined in clause (j) of Section 8(1) of the RTI Act.

- We are in agreement with the CIC and the courts below that the details called for by the petitioner i.e. copies of all memos issued to the third respondent, show cause notices and orders of censure/punishment etc. are qualified to be personal information as defined in clause (j) of Section 8(1) of the RTI Act. The performance of an employee/officer in an organization is primarily a matter between the employee and the employer and normally those aspects are governed by the service rules which fall under the expression “personal information”, the disclosure of which has no relationship to any public activity or public interest. On the other hand, the disclosure of which would cause unwarranted invasion of privacy of that individual. Of course, in a given case, if the Central Public Information Officer or the State Public Information Officer of the Appellate Authority is satisfied that the larger public interest justifies the disclosure of such information, appropriate orders could be passed but the petitioner cannot claim those details as a matter of right.

- The details disclosed by a person in his income tax returns are “personal information” which stand exempted from disclosure under clause (j) of Section 8(1) of the RTI Act, unless involves a larger public interest and the Central Public Information Officer or the State Public Information Officer or the Appellate Authority is satisfied that the larger public interest justifies the disclosure of such information.”

A careful reading of the law shows that personal Information held by a public authority may be denied under section 8(1)(j), under the following two circumstances:

- Where the information requested, is personal information and the nature of the information requested is such that, it has apparently no relationship to any public activity or interest; or

- Where the information requested, is personal information, and the disclosure of the said information would cause unwarranted invasion of the privacy of the individual.

If the information is personal information, it must be seen whether the information came to the public authority as a consequence of a public activity. Generally most of the information in public records arises from a public activity. Applying for a job, or ration card are examples of public activity. However there may be some personal information which may be with public authorities which is not a consequence of a public activity, eg. Medical records, or transactions with a public sector bank. Similarly a public authority may come into possession of some information during a raid or seizure which may have no relationship to any public activity.

Even if the information has arisen by a public activity it could still be exempt if disclosing it would be an unwarranted invasion on the privacy of an individual. Privacy is to do with matters within a home, a person’s body, sexual preferences etc as mentioned in the apex court’s earlier decisions in Kharak Singh and R.Rajagopal cases. This is in line with Article 19 (2) which mentions placing restrictions on Article 19 (1) (a) in the interest of ‘decency or morality’. If however it is felt that the information is not the result of any public activity, or disclosing it would be an unwarranted invasion on the privacy of an individual, it must be subjected to the acid test of the proviso: Provided that the information, which cannot be denied to the Parliament or a State Legislature shall not be denied to any person.

The proviso is meant as a test which must be applied before denying information claiming exemption under Section 8 (1) (j). Public servants have been used to answering questions raised in Parliament and the Legislature. It is difficult for them to develop the attitude of answering demands for information from citizens. Hence before denying personal information, the law has given an acid test: Would they would give this information to the elected representatives. If they come to the subjective assessment, that they would provide the information to MPs and MLAs they will have to provide it to citizens, since the MPs and MLAs derive legitimacy from the citizens.

Another perspective is that personal information is to be denied to citizens based on the presumption that disclosure would cause harm to some interest of an individual. If however the information can be given to legislature it means the likely harm is not much of a threat since what is given to legislature will be in public domain. It is worth remembering that the first draft of the bill which had been presented to the parliament in December 2004 had the provision as Section 8 (2) and stated: (2) Information which cannot be denied to Parliament or Legislature of a State, as the case may be, shall not be denied to any person. In the final draft passed by parliament in May 2005, this section was put as a proviso only for section 8 (1) (j). Thus it was a conscious choice of parliament to have this as a proviso only for Section 8 (1) (j). It is necessary that when information is denied based on the provision of Section 8 (1) (j), the person denying the information must give his subjective assessment whether it would be denied to Parliament or State legislature if sought.

It is worth noting that in the Privacy bill 2014 it was proposed that Sensitive personal data should be defined as Personal data relating to: “(a) physical and mental health including medical history, (b) biometric, bodily or genetic information, (c) criminal convictions (d) password, (e) banking credit and financial data (f) narco analysis or polygraph test data, (g) sexual orientation. Provided that any information that is freely available or accessible in public domain or to be furnished under the Right to Information Act 2005 or any other law for time being in force shall not be regarded as sensitive personal data for the purposes of this Act”.

Only if a reasoned conclusion is reached that the information has no relationship to any public activity or that disclosure would be an unwarranted invasion on the privacy of an individual a subjective assessment has to be made whether it would be given to Parliament or State legislature. If it is felt that it would not be given, then an assessment has to be made as Section 8 (2) whether there is a larger public interest in disclosure than the harm to the protected interest. If no exemption applies there is no requirement of showing a larger public interest.

In the impugned judgment a RTI request for copies of all memos, show cause notices, orders of censure/punishment, assets, income tax returns, details of gifts received etc. of a public servant was denied. The court has ruled without giving any legal arguments merely by saying that this is personal information as defined in clause (j) of Section 8(1) of the RTI Act and hence exempted. The only reason ascribed in this is that the court agrees with the Central Information Commission’s decision. Such a decision does not form a precedent which must be followed. It cannot be justified by Article 19 (2) of the constitution or by the complete provision of Section 8 (1) (j). As per the RTI act denial of information can only be on the basis of the exemptions in the law. The court has denied information by reading Section 8 (1) (j) as exempting:

“information which relates to personal information the disclosure of which has no relationship to any public activity or interest, or which would cause unwarranted invasion of the privacy of the individual unless the Central Public Information Officer or the State Public Information Officer or the appellate authority, as the case may be, is satisfied that the larger public interest justifies the disclosure of such information:

Provided that the information, which cannot be denied to the Parliament or a State Legislature shall not be denied to any person.”

There are no words in the judgment,- or the CIC decision which it has accepted,- discussing whether the disclosure has any relationship to a public activity, or if disclosure would be an unwarranted invasion on the privacy. The words which have been struck above have not been considered at all and information was denied merely on the basis that it was personal information. Worse still the proviso ‘Provided that the information…..’ (underlined above) has not even been mentioned and while quoting the entire Section 8 (1) the proviso has been missed . Effectively only 40 of the 87 words in this section were considered. This proviso is very important and the court should have addressed it. I would also like to quote the ratio of R Rajagopal and Anr. v state of Tamil Nadu (1994), SC

The ratio of this judgement was:

“28. We may now summarise the broad principles flowing from the above discussion:

(1) the right to privacy is implicit in the right to life and liberty guaranteed to the citizens of this country by Article 21. It is a “right to be let alone.” A citizen has a right to safeguard the privacy of his own, his family, marriage, procreation, motherhood, child bearing and education among other matters. None can publish anything concerning the above matters without his consent – whether truthful or otherwise and whether laudatory or critical. If he does so, he would be violating the right to privacy of the person concerned and would be liable in an action for damages Position may, however be different, if a person voluntarily thrusts himself into controversy or voluntarily invites or raises a controversy.

(2) The rule aforesaid is subject to the exception, that any publication concerning the aforesaid aspects becomes unobjectionable if such publication is based upon public records including Court records. This is for the reason that once a matter becomes a matter of public record, the right to privacy no longer subsists and it becomes a legitimate subject for comment by press and media among others. We are, however, of the opinion that in the interest of decency (Article 19(2)) an exception must be carved out to this rule, viz., a female who is the victim of a sexual assault, kidnap, abduction or a like offense should not further be subjected to the indignity of her name and the incident being published in press/media.

(3) There is yet another exception to the Rule in (1) above – indeed, this is not an exception but an independent rule. In the case of public officials, it is obvious, right to privacy, or for that matter, the remedy of action for damages is simply not available with respect to their acts and conduct relevant to the discharge of their official duties.”

Public record as defined in the Public Records Act is any record held by any Government office. This judgement at point 2 clearly states that for information in public records, the right to privacy can be claimed only in rare cases. This is similar to the proposition in Section 8 (1) (j) which does not exempt personal information which has relationship to public activity or interest. It also talks of certain kinds of personal information not being disclosed which has been covered in the Act by exempting disclosure of personal information which would be an unwarranted invasion on the privacy of an individual. At point 3 it categorically emphasizes that for public officials the right to privacy cannot be claimed with respect to their acts and conduct relevant to the discharge of their official duties. The Girish Deshpande judgment is clearly contrary to the earlier judgment R.Rajagopal judgment, since it accepts the claim of privacy for Public servants for matters relating to public activity which are on Public records

- 2. The Supreme Court judgement in the ADR/PUCL Civil Appeal 7178 of 2001 has clearly laid down that citizens have a right to know about the assets of those who want to be Public servants (stand for elections). It should be obvious that if citizens have a right to know about the assets of those who want to become Public servants, their right to get information about those who are Public servants cannot be lesser. This would be tantamount to arguing that a prospective groom must declare certain matters to his wife-to-be, but after marriage the same information need not be disclosed!

The Girish Ramchandra Deshpande judgment should not be treated as a precedent which must be followed for the following reasons:

- It is devoid of any detailed reasoning and does not lay down a ratio.

- It does not analyse whether a public servant’s work and assets is information which is a public activity or not. The judgment when stating that certain matters are between the employee and the employer misses the fact that the employer is the ‘people of India’.

- It has completely forgotten the proviso to Section 8 (1) (j) which requires subjecting a proposed denial to this acid test.

- It has not considered the clear ratio of the Rajagopal judgment or the ADR/PUCL judgment.

A major provision of the RTI Act has been amended by a judicial pronouncement which appears to be flawed. A major tool of citizens to bring the shenanigans, arbitrary and corrupt acts of public servants has been affected adversely without a proper reasoning. Commissioners must discuss this and it must be recognized that Girish Ramchandra Deshpande does not lay down the law on Section 8 (1) (j) of the RTI Act., and it is contrary to the ratio of the R.RajagopaI and ADR judgments. A five judge bench has ruled in P. Ramachandra Rao v. State of Karnataka case no. appeal (crl.) 535.: “Courts can declare the law, they can interpret the law, they can remove obvious lacunae and fill the gaps but they cannot entrench upon in the field of legislation properly meant for the legislature.”

Shailesh Gandhi shaileshgan@gmail.com

Former Central Information Commissioner

[1] Special Leave Petition (Civil) No. 27734 of 2012; Girish Ramchandra Deshpand Versus Cen. Information Commr. & Ors; KS Radhakrishnan & Dipak Misra; 3 October 2012; (2013) 1 SCC 212

‘Misuse’ of RTI

‘Misuse’ of RTI

As an Information Commissioner who dealt with over 20000 cases I had the opportunity of interacting with a large number of RTI users and Public Information Officers (PIOs).

Generally PIOs would refer to most applicants who file RTI applications regularly as blackmailers, harassers and those who were misusing RTI. I would broadly divide those who filed a large number of RTI applications in the following categories:

- Those who filed RTI applications with the hope of exposing corruption or arbitrariness and hoped to improve and correct governance.

- Those who filed RTI applications repetitively to correct a wrong which they perceived had been done to them. Their basic intention is to get justice for themselves.

- Those who used RTI to blackmail people. This category largely targets illegal buildings, mining or some other activity which runs foul of the law.

- Those who use this to harass a public official to get some undue favour.

All these categories together comprise around 20% of the total appeals and complaints before the Commission. These represent persistent users of RTI who are generally knowledgeable about appeals and procedures. Nobody will deny that the first category certainly deserves to be encouraged. In the second category there are some who have been able to get corrective action and some whose grievance may defy resolution. When faced with such applicants, PIOs should speak to the concerned officer to evaluate whether the grievance can be redressed. Generally most of us have a strong aversion for the third and fourth category who are making it a money-earning racket or putting pressure to get an undue favour. The last two categories certainly does not exceed 10% of the total appeals and complaints. I would like to note that most of the average citizens who do not get information are unaware of the process of appeals. Over 40% of those who attempt filing appeals at CIC are discouraged with imperious returns. Thus it appears that the third and fourth category will be much smaller than 10% in terms of RTI applications.

I would argue that in the implementation of most laws some people will misuse its provisions. The police often misuse their powers to subvert the law, and so also criminals misuse our judicial system to prolong trials. The misuse of any laws is largely dependent on the kind of people in a society and whether the justice system has the capability of punishing wrongdoers. There are people who go to places of worship with the sole objective of committing theft or other crimes. But society does not define these as the main characteristic of temples. Is it reasonable to expect that only angels will use RTI?

To be able to blackmail an officer or someone who has indulged in an illegal activity, there are some illegal actions. Noticing and curbing these is the job of various government officers and the citizen is actually acting as a vigilance monitor. I have often questioned government officers how the blackmailers operate. They state that the RTI blackmailer threatens an illegal action with exposure and thereby extorts money. I have sometimes wondered why society has such touching empathy for the victims who have committed illegal acts. The fourth category must be discouraged and Information Commissioners can do this fairly easily. This can be done by either ordering an inspection of the files by the appellant.

Two simple tips to PIOs to handle repetitive RTI queries:

- Ensuring that the information is provided in less than 10 days by taking applications from such applicants on priority. Ensuring that letter asking for additional fees is sent well in time. I have found such an approach usually leading to reduction of such applications. If however this does not have any effect, then the matter should be highlighted before the Information Commissioner in second appeal.

- Another good practice which could be adopted would be to upload all queries and the replies on the website. Where information has already been provided applicants may not ask for it. Even if they do ask, the PIO would find it easy to provide it. Besides in a few cases where an applicant is filing what appears to be frivolous or repetitive applications, this would be a restraint since it would expose such applicants.

- If someone is indeed filing requests for the same information repetitively make him pay each time.

The constant refrain of some people to highlight ‘misuse’ of RTI is an attempt to muzzle the citizen’s fundamental right. Freedom of speech and media which also are covered under Article 19 (1) (a) have been expanding with time. There is a national debate when a movie is subjected to cuts or people or media are muzzled by government, political class or ruffians. Yet the nation goes along with this big lie of RTI threatening the peace, harmony and integrity of India. If RTI is curbed the day is not far when we will have to give reasons to speak and establish our identity. A person can be defamed by speech or writing. Should we now have a demand to allow only those persons to speak who give reasons and established their identity ? On the other hand RTI can only seek information which exists on records.

One of the most problematic statements by the Supreme Court is quoted in many places: “Indiscriminate and impractical demands or directions under RTI Act for disclosure of all and sundry information (unrelated to transparency and accountability in the functioning of public authorities and eradication of corruption) would be counter-productive as it will adversely affect the efficiency of the administration and result in the executive getting bogged down with the non-productive work of collecting and furnishing information. The Act should not be allowed to be misused or abused, to become a tool to obstruct the national development and integration, or to destroy the peace, tranquility and harmony among its citizens. Nor should it be converted into a tool of oppression or intimidation of honest officials striving to do their duty. The nation does not want a scenario where 75% of the staff of public authorities spends 75% of their time in collecting and furnishing information to applicants instead of discharging their regular duties. “

This needs to be contested. The statement “should not be allowed to be misused or abused, to become a tool to obstruct the national development and integration, or to destroy the peace, tranquility and harmony among its citizens” would be appropriate for terrorists, not citizens using their fundamental right to information. There is no evidence of RTI damaging the nation. As for the accusation of RTI taking up 75% of time, I did the following calculation: By all accounts the total number of RTI applications in India is less than 10 million annually. The total number of all government employees is over 20 million. Assuming a 6 hour working day for all employees for 250 working days it would be seen that there are 30000 million working hours. Even if an average of 3 hours is spent per RTI application (the average is likely to be less than two hours) 10 million applications would require 30 million hours, which is 0.1% of the total working hours. This means it would require 3.2% staff working for 3.2% of their time in furnishing information to citizens. This too could be reduced drastically if computerised working and automatic updating of information was done as specified in Section 4 of the RTI Act. It is unfortunate that the apex court has not thought it fit to castigate public authorities for their brazen flouting of their obligations under Section 4, but upbraided the sovereign citizens using their fundamental right.

I would submit that the powerful find RTI upsetting their arrogance and hence try to discredit it by often talking about its misuse. There are many eminent persons in the country, who berate RTI and say there should be some limit to it. It is accepted widely that freedom of speech is often used to abuse or defame people. It is also used by small papers to resort to blackmail. The concept of paid news has been too well recorded. Despite all these there is never a demand to constrict freedom of speech. But there is a growing tendency from those with power to misinterpret the RTI Act almost to a point where it does not really represent what the law says. There is widespread acceptance of the idea that statements, books and works of literature and art are covered by Article 19 (1) (a) of the constitution, and any attempt to curb it meets with very stiff resistance. However, there is no murmur when users of RTI are being labelled deprecatingly, though it is covered by the same article of the constitution. Everyone with power appears to say: “I would risk my life for your right to express your views, but damn you if you use RTI to seek information which would expose my arbitrary or illegal actions.“ An information seeker can only seek information on records. We rate amongst the top five in the world in terms of provisions of the law and 66 in terms of implementation. Any amendments or obstructionist acts will push us closer to our low rank in implementation.

I would also submit that such frivolous attitude towards our fundamental right is leading to an impression that RTI needs to be curbed and its activists maybe deprecated, attacked or murdered.

Shailesh Gandhi

How I became an Information Commissioner

Some friends wonder how I have the gall to be critical of the lack of process in selecting Information Commissioners, since they believe I must have resorted to influence and patronage for my selection.

Let me detail the story of how i got selected:

In the first week of August 2008 Arvind Kejriwal learnt that the government had decided on the names of four persons whom they would appoint as Central Information Commissioners. These were:

- Satyananda Mishra

- M.L.Sharma

- Annapurna Dixit

- R.B.Sreekumar

I believe there is a tacit understanding between the ruling party and the opposition on such matters and overall there is a certain give and take in matters of appointments. Arvind discussed with me that though we had been fighting for appointment of good Commissioners and transparency in the selection process we were not making any headway. He therefore suggested that we propose four names from civil society. We got together a list of credible persons and Arvind arranged to get letters sent to the PM, Advani and Prithvraj Chavan by some prominent civil society members recommending these.

On 20 August Prithviraj Chavan asked for a meeting of the Selection Committee to be called on 21 August at 6.00pm. I have heard that on 20 night the four names were shown to LK Advani. Advani strongly objected to the name of Sreekumar since he had been a senior police officer in Gujarat at the time of the Godhra riots and openly criticized Narendra Modi. He said he would oppose Sreekumar’s selection and said, ‘Why not one of the names suggested by civil society?’ The selection Committee meeting was not held on 21 August.

I did not know Prithviraj Chavan, nor did he know me. Whether he made any checks about the other three members of our panel I do not know. As for me, he called up a business person in Mumbai and asked him what kind of person I was. This person had never met me, but based on what he had read in the papers he said I would be a good choice. After this Prithviraj Chavan called me and asked me if I would accept if I was selected as a Central Information Commissioner, and I said yes.

On 27 August a meeting was called and my name was put in place of R.B. Sreekumar.

Some of this information is available at http://persmin.gov.in/DOPT/RTICorner/ImpFiles/6_4_2008_IR_Vol_I_Noting.pdf

I can assure all of you, that I did not use any influence or network. It was a random occurrence, but my selection was also without any process and a random occurrence.

The record also shows Asok K Mahaptra’s name and I do not have any knowledge of how his name was dropped. I would urge RTI activists who have an understanding of the legal issues of the law to apply for the positions of Information Commissioners. Ciitizens should put forward names of persons with a background in transparency and build pressure

I would also like to point out two matters as a personal clarification:

I had informed the government that I was paying volunteers to work with me is mentioned on page 22. Whereas in 2007-2008 five Commissioners disposed 7722 cases I alone averaged about 5400 cases per year.

All my emails are in public domain

Judiciary and RTI

The Supreme Court of India consistently held from 1975 to 2005 that RTI is a fundamental right of citizens. However certain decisions and pronouncements of the Courts in the last four years could weaken this powerful fundamental right. These should be discussed by RTI users and the legal fraternity.

Challenging decisions of the Information Commission and stay orders: The law provides for no appeals against the decisions of the Commission. However these decisions are being challenged in High Courts through writ petitions by many public authorities to deny information to citizens. In most of these cases a stay is obtained ex-parte. At times, Commissions have been stopped from even investigating matters before them. These cases die down as most of the applicants are unable to respond effectively in Courts for lack of resources.

There is a need for the court to examine prima facie whether the grounds fall in the writ jurisdiction of a Court, and whether any irreparable harm would befall the petitioner if a stay is not given, since these continue for many years. The Supreme Court has stated many times that an essential requirement for any judicial, quasi-judicial or administrative order is that reasons must be provided. There are a number of High Court orders staying the disclosure of information as per the orders of the information commissions where no reasons are given.

Disclosure of Information: The law has strong provisions to ensure disclosure of most information, and lays down in Section 22 that its provisions supersede all earlier laws. It further stipulates that denial of information can only be done based on the provisions of Section 8 or 9. Additionally the onus to justify denial of information is on the PIO in any appeal proceedings. Denial of information should be rare. An analysis of the judgements of the Supreme Court on the RTI Act shows that out of sixteen judgements disclosure of information was ordered only in the judgement mentioned below at number 1. I am giving my comments on three judgements below:

1 In Appeal No. 6454 of 2011 the Court held, “Some High Courts have held that Section 8 of RTI Act is in the nature of an exception to Section 3 which empowers the citizens with the right to information, which is a derivative from the freedom of speech; and that therefore Section 8 should be construed strictly, literally and narrowly. This may not be the correct approach.” I feel the earlier approach where exemptions are interpreted narrowly, since these abridge a fundamental right of citizens. Another strong statement in the said judgment is : ‘Indiscriminate and impractical demands or directions under RTI Act for disclosure of all and sundry information (unrelated to transparency and accountability in the functioning of public authorities and eradication of corruption) would be counter-productive as it will adversely affect the efficiency of the administration and result in the executive getting bogged down with the non-productive work of collecting and furnishing information. The Act should not be allowed to be misused or abused, to become a tool to obstruct the national development and integration, or to destroy the peace, tranquility and harmony among its citizens. Nor should it be converted into a tool of oppression or intimidation of honest officials striving to do their duty. The nation does not want a scenario where 75% of the staff of public authorities spends 75% of their time in collecting and furnishing information to applicants instead of discharging their regular duties.’

A study by RAAG has shown that about 50% of the RTI applications are made since the departments do not discharge their duty under Section 4 of the RTI Act which mqndates disclosure of most of the information suo moto as per the law. About 25% of the applications seek information about citizens trying to obtain their delayed ration cards, progress of their application for various services or complaints of illegal activities for which the government departments should have replied. There is no condemnation of the officers who,- often for not receiving bribes,- do not do their duty, but the citizen using his fundamental right is strongly admonished without any evidence or basis.

2) In the Girish Ramchandra Deshpande judgement given in October 2012 the Court has held that copies of all memos, show cause notices and orders of censure/punishment, assets, income returns, details of gifts received etc. by a public servant are personal information exempted from disclosure as per Section 8(1) (j) of the RTI Act. It further states that these are matters between the employee and the employer, without realising that the employer is the citizen,- the master of democracy,- who provides legitimacy to the government. This judgement appears to have neither legal reasoning, nor a legal principle and is based on concurring with the denial of information by the information commission. The ratio of the R.Rajagopal judgement given by the Supreme Court in 1994 clearly lays down that no claim to privacy can be claimed for personal information on public records by public servants. It appears this judgement was not presented to the Court.

In Section 8 (1) (j) there is a proviso ‘that the information, which cannot be denied to the Parliament or a State Legislature shall not be denied to any person”. There is no mention of this proviso in the judgement and no word that the court was satisfied that this information would not be provided to parliament or state legislature.

3) A Madras High Court judgement on 17 September 2014 has caused considerable confusion since it said that citizens must give reasons for seeking information. This was in direct violation of Section 6 (2) of the Act which states,” An applicant making request for information shall not be required to give any reason for requesting the information”. The court realised this mistake in a week and withdrew this observation. This judgement not only violated the RTI Act it was in violation of Article 19 (1) (a) of the constitution.

I hope the courts will take an active part in expanding the reach and scope of RTI. If they interpret the RTI Act giving more importance to exemptions and widening their scope, this great law may become ‘Right to Denial of Information’. This would be a sad regression for democracy.

Shailesh Gandhi

RTI activist and Former Central Information Commissioner