Timebound Hindu Article

Revving up the judicial juggernaut 19 August 2014 Oped

हिन्दी समाचार – समाचार लेख Google हिंदी वेब अभी hindiweb.com

SHAILESH GANDHI

With citizens suffering acutely because of delays in court trials, it is time to fix accountability of the judges

Recently, the Supreme Court refused to fast-track criminal cases against Members of Parliament, saying the manpower in trial courts and infrastructure was inadequate. Prime Minister Narendra Modi had, on June 11, sought to expedite trials of pending cases against MPs within a year. But that could have meant pushing other cases back in the queue. As the apex court rightly observed, there are other categories where criminal trials need to be expedited, such as women and senior citizens.

The Supreme Court needs to make a commitment on the need to deliver time-bound justice. But is that possible?

Analysis of data

To understand this, I did some number crunching, with the objective of trying to estimate the number of judges required for deliverance of justice on time. I used the Supreme Court data for 12 quarters, from July 2009 to June 2012.

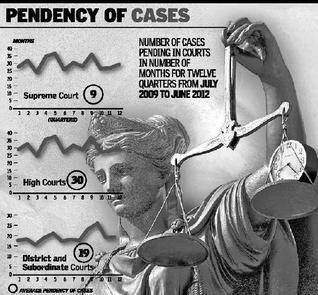

I made note of new cases instituted in each quarter and disposed and pending cases in the Supreme Court, High Courts and district and subordinate courts. I divided the number of cases disposed per quarter to arrive at the figure of average monthly disposal of cases. Then I divided the number of pending cases with this figure to estimate monthly pendency.

For each quarter, I realised, no case appeared in backlog for more than 36 months. And yet, many people have had cases continuing for over 10 years because of no adherence to chronologically clear cases.

The average pendency for the Supreme Court, High Courts and district and subordinate courts for the period July 2009 to June 2012 comes to 9 months, 30 months, and 19 months respectively.

The legal profession is aghast when one talks about measuring such numbers, on the ground that the differences in cases is vast. Many in the legal fraternity say one cannot apply mathematical analysis to understand this. However, over a large number of courts and cases, the large variations due to different cases would even out and can be used to compare or find possible solutions.

Besides, the evaluation is based on 12 quarters over three years, and appears to show some consistency. This data appears to show some consistency as the graphs show.

This appears to indicate that if the principle of ‘first in, first out’ (FIFO) could be strictly followed, this may be the time required to decide a case in a court.

This would not be feasible completely, but there can be no justification for many cases taking more than double the average time in the courts. Courts should lay down a discipline that almost no case should be allowed to languish for more than double the average time taken for disposals. At present, the listing of cases is being done by the judges, and no human being can really do this exercise rationally, given the mass of data. It would be sensible to devise a fair criterion and incorporate this in computer software, which would list the cases and also give the dates for adjournments based on a rational basis. This would result in removing much of the arbitrariness and also reduce the power of some lawyers to hasten or delay cases as per their will. If done, the maximum time the three courts would take to decide on a case would be 18 months, 60 months, and 38 months. The average vacancies in the three levels are 15 per cent for the Supreme Court, 30 per cent for the High Courts and over 20 per cent for the district and subordinate courts.

Filling in vacancies

When citizens are suffering acutely because of the huge delays in the judicial system, there can be no justification for such high levels of sanctioned positions being vacant. The dates of retirement of judges are known in advance and hence the vacancies are largely because of neglect. After filling the vacancies, if courts stick to their avowed judgments to allow adjournments rarely, it should certainly be possible to increase the disposals by at least 20 per cent. Basically, if courts follow the principle of FIFO, the judiciary could deliver in a reasonable time.

That is why courts must accept the discipline that over 95 per cent of the cases will be settled in less than double the average pendency. Then, reasonable equity could be provided to citizens and Article 14 actualised in courts. The listing of cases should be done by a computer programme, with judges having the discretion to override it in only 5 per cent of cases.

Also, vacancies in the sanctioned strength of judges should be less than 5 per cent. Adjournments should be rare, and the maximum number ought to be fixed by a computer. A calculation can be done to see the number of judges required to bring the average pendency in all courts to less than one year. Most probably, an increase of about 20 per cent judges in High Courts and lower judiciary could bring down the average pendency to less than a year. The number of disposals per judge and per court along with data of pending cases, giving details of the periods since institution, should be displayed by the courts on their websites.

That would be meaningful judicial accountability.

(Shailesh Gandhi is former Central Information Commissioner.)

Courts should lay down a discipline that almost no case should be allowed to languish for more than double the average time taken for disposals